Lake Pillans with wood duck blast furnace in background. (Tracie McMahon)

By Tracie McMahon

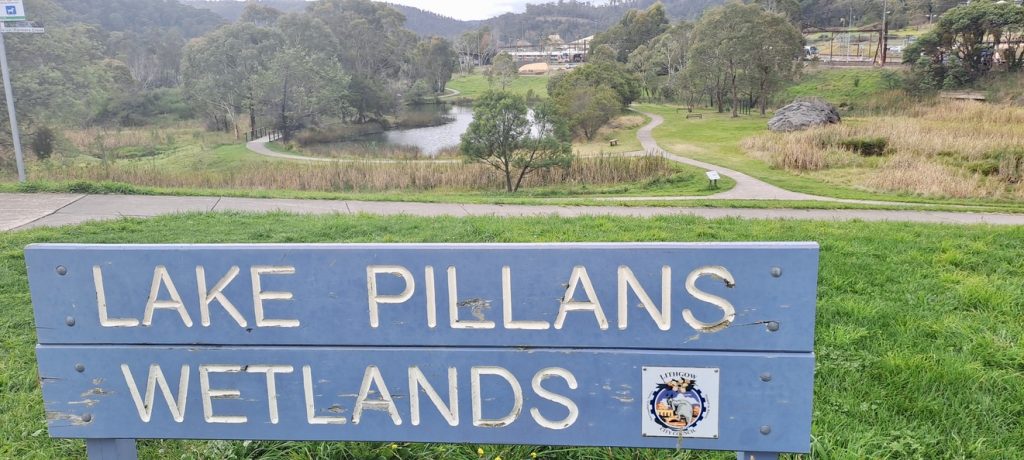

Lake Pillans is an integral part of Lithgow’s story. It was dammed in 1911 as a water supply for the Eskbank Ironworks and was known locally as Little Coogee, popular for boating and swimming; its appeal boosted by the hot water returning from engine houses at the furnace.

Today, thanks to support provided by the private sector, government organisations and many community volunteers and organisations, it is a functioning wetland system, providing habitat for local wildlife and an effective way to detain floodwater and filter stormwater.

Lake Pillans is interesting for both its industrial history and the impact of the 2019/20 Bushfire which destroyed much of the native revegetation work organised by Lithgow and Districts Landcare groups since 2012.

Lake Pillans Wetlands (Tracie McMahon)

In April the Maldhan Ngurr Ngurra Lithgow Transformation Hub launched its first citizen science activity for 2023: the Lake Pillans BioBlitz. I spoke with Alice Blackwood, ecologist and Field Technician at Western Sydney University about citizen science and their findings at Lake Pillans.

Alice explains that citizen science involves members of the public recording observations, which are then verified before being added to a pool of data. Often under the direction of professional scientists, citizen science can also be done independently. The types of data are key, so things like location and different features of a plant or animal are important to making the observations meaningful for research. It’s not just about taking the best picture.

Alice explains that the BioBlitz at Lake Pillans is one of a series of events the Transformation Hub is planning to document the biodiversity in the Lithgow Region, in a project named ‘Regenerating Lithgow’. This includes participating in the Great Southern BioBlitz in November; an international effort to record all living species within several designated areas across the Southern Hemisphere in one intensive period of observation.

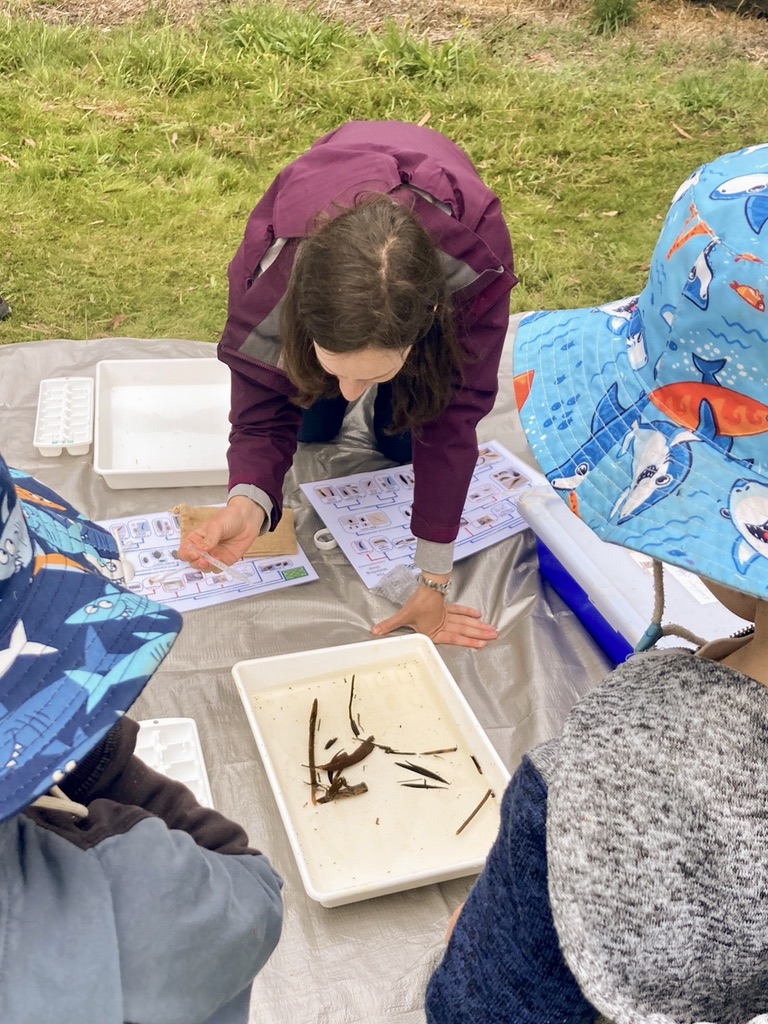

I wonder how an ordinary citizen like me could help, given my zero training in biology. Alice tells me: “there are no identification skills required, just curiosity. Everyone can contribute. At the Lithgow event we were fortunate to have an entomologist along, so we were also able to focus on insects.” Alice has expertise in water bugs, so participants spent time on their hands and knees peering down microscopes identifying bugs in samples of water Alice had drawn from the lake.

Alice Blackwood wth participants observing waterbugs in samples extracted from Lake Pillans. (Lithgow Transformation Hub)

I’m relieved that there is someone along to show you how to observe, but I wonder how the scientists keep up with all the observations. Alice tells me that is a big advantage of citizen science. Observations can be recorded anywhere, anytime and by anyone, using iNaturalist; an app (and website) developed in conjunction with the CSIRO, the global iNaturalist Network and the Atlas of Living Australia. iNaturalist provides information to suggest an identification. You identify your photo at the level you are confident with (eg. insect). Once the observation is uploaded and you’ve provided your identification, those with more knowledge and skills about insects will pick it up and take it from there to determine what type of insect it is.

The public don’t just upload observations but also help each other by suggesting species identification. Once there is sufficient consensus, an observation will be marked as research grade and uploaded to the Atlas of Living Australia. Alice shows me how easy it is to use. I’m thrilled. I had used iNaturalist to identify plants on bushwalks but hadn’t thought about it as a two-way process. I don’t need to stop at finding out the name of a plant, I could provide valuable information to the Atlas of Living Australia. Alice nods. “It goes from: I wonder what that weird thing is, to data.” I take a photo of something that looks interesting, and the app uses AI to compare with information held on the Atlas of Living Australia (a compilation of recorded sightings of flora and fauna). I get to select from a list of suggestions, so there’s a back and forth process between the AI and the citizen scientist before uploading for a specialist to check and verify.

Alice Blackwood leans in to photograph an insect in the Permaculture Hub ready to upload to iNaturalist. (Tracie McMahon)

So what did they find at Lake Pillans? Alice tells me she was surprised how easy it was to get new and interesting observations. In three hours, the group of twelve made 86 verifiable observations and found 72 different species. These included the first recorded sighting of an Emperor Gum Moth in Lithgow and evidence of two bugs that are important indicators of water quality: sightings of mayflies and caddisflies suggest that the water of Lake Pillans is in a healthy state.

I am impressed. I suspect I may have come across a supergroup of nature observers. Alice assures me they were ordinary citizens: locals, visitors, tourists, babies, grandparents, and everything in between. The key ingredient is curiosity. Most of the participants wandered about taking photos and doing their own thing. A few had a specific interest in macrophotography, but most were just keen to learn more about the wetland environment.

Alice suspects the participants will upload more as they return to the site, their curiosity empowered with iNaturalist skills. She suggests I could pop down and add a few. At home, I check on the iNaturalist website, to optimise my next visit to the lake. I am amazed to find I am one of almost 70,000 observers in Australia. Some of the plant observations I did earlier are included in the 50,000 species identified to research grade. I was feeling a bit chuffed with my 52 individual observations until I read the next statistic: the site has almost 5.5 million observations in Australia alone! I decide Alice is right, I had better get down to the lake and do some citizen science!

Alice Blackwood at the Maldhan Ngurr Ngurra Transformation Hub showing me the iNaturalist website and project they are working on. (Tracie McMahon)

If you would like to contribute to citizen science at Lake Pillans, the BioBlitz is listed as a project in iNaturalist. Once logged into iNaturalist you can join by selecting projects in the dropdown menu and searching Lake Pillans BioBlitz. Any data collected in this project will be added to the bigger ‘Regenerating Lithgow’ project, which will link to citizen science events the Transformation Hub has coming up.

If you would like to get involved in these, the Maldhan Ngurr Ngurra Lithgow Transformation Hub can be contacted on 6354 4505, and you can follow them on Facebook for alerts.

But you do not have to wait for an event to learn about the biodiversity of the Lithgow region or add to existing data. iNaturalist is accessible 24/7!

Lake Pillans (Tracie McMahon)

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.

2 comments

Pingback: Maldhan Ngurr Ngurra Lithgow Transformation Hub: An Evolving Story of Community & Learning – Lithgow Area Local News

Pingback: Postcards from the Past, Present and Future - Lithgow Area Local News