Earth Tongues poking up from beneath leaf litter on a bush track. (Tracie McMahon)

Mushroom season may be over, but edible mushrooms are just one kind of fungi, as Tracie McMahon found out when she attended a mycology workshop run by Lithgow Oberon Landcare and Maldhan Ngurr Ngurra Lithgow Transformation Hub.

Key Points:

- From cradle to grave fungi are critical to our lives.

- In a recent mycology workshop in Lithgow participants learnt how to identify specimens and to ensure the ongoing survival of this vital organism.

- We can protect fungi with good boot hygiene and not collecting from nature without authority.

Share this article:

Mycology is the study of fungi, and it’s trending. Foodies are delighting in earthy flavours, photographers in unique imagery, and scientists in the extraordinary connections nick-named by scientific journal Nature the ‘wood-wide-web’.

This web or mycorrhizal network is a mutual relationship between fungi and flora, in which information is exchanged. Threats such as pests or diseases are communicated through sugars, water and chemicals. As Peter Wohlleben writes in his international bestseller The Hidden Life of Trees, it is as if “the fungi are pursuing their own agendas … in favour of conciliation and equitable distribution of resources.”

To support local interest in fungi, Maldhan Ngurr Ngurra Lithgow Transformation Hub and Lithgow Oberon Landcare facilitated a free workshop, to help people understand the importance of fungi and ensure they were looking after themselves and the fungi.

At the fully subscribed workshop scores of people were able to see a variety of fungi and were introduced to the complexity of identification. One of the key takeaways from the session was there are no simple rules to tell if something is toxic. Don’t eat fungi you find unless you are 100% confident it is an edible species and one you are familiar with.

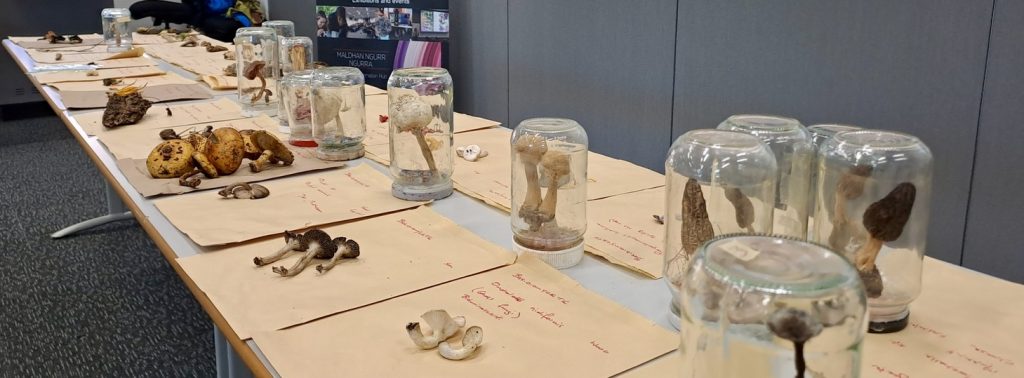

Fungi collected under license by Gemma Williams and displayed at the workshop. (Tracie McMahon)

Michael Priest, mycologist and educator, discussed the diversity of fungi and common misconceptions. Fungi are not plants, as they do not rely on chlorophyll for survival. They have evolved to survive in every landscape on Earth, including ocean floors, the Arctic and Antarctica. It is estimated that there are approximately 15,000 species of fungi with visible fruiting bodies (macro-fungi like mushrooms and puffballs) of which only 30% have been identified. The largest recorded fungus nicknamed ‘the humongous fungus’, covers 9 square kilometres in a forest in Oregon and is estimated to be between 2,000 and 8,500 years old.

Ninety percent of Australia’s plants are dependent on fungi for survival. Some animal species, such as the Potoroo, depend almost entirely on fungi for food. Fungi also decompose waste material. Michael explained that without fungi the Earth would be “piled high” with dead trees, animals, and leaf litter. The process of decomposition releases carbon and nitrogen into the soil, providing elements essential for plants to grow and thrive. Many agricultural and medical products are also dependent on fungi. Without fungi “there would be no antibiotics, bread, cheese, beer or wine. Quite simply, life as we know it, would end.”

Michael Priest, mycologist and educator, presents at the mycology workshop. (Tracie McMahon)

As scientists learn more about fungi and the mycorrhizal network, they are also discovering new applications. Fungi have been used to break down radioactive materials and plastics, to absorb heavy metals from soil and to rehabilitate mine sites. Steve Fleischmann, Landcare Coordinator at Lithgow Oberon Landcare, explained that fungi are actively used in regenerative landcare practices. Minimal impact work, such as construction of water channels (swales) and strategic plantings, leads to fungi “popping-up”. Pollinator insects then appear, followed by other plant species. There is still much to learn, but he says we are just beginning to understand the deep complex relationships that exist between flora and fauna.

For those who are content to leave the scientists and land managers to their research, fungi provide another attraction. They are beautiful and photogenic. At the mycology workshop, Gemma Williams, a self-described “Veterinarian with a keen interest in mycology”, presented a slideshow of her mycological tourism, to the delighted oohs and aahs of the audience.

Gemma Williams presenting some of her stunning images of fungi. (Tracie McMahon)

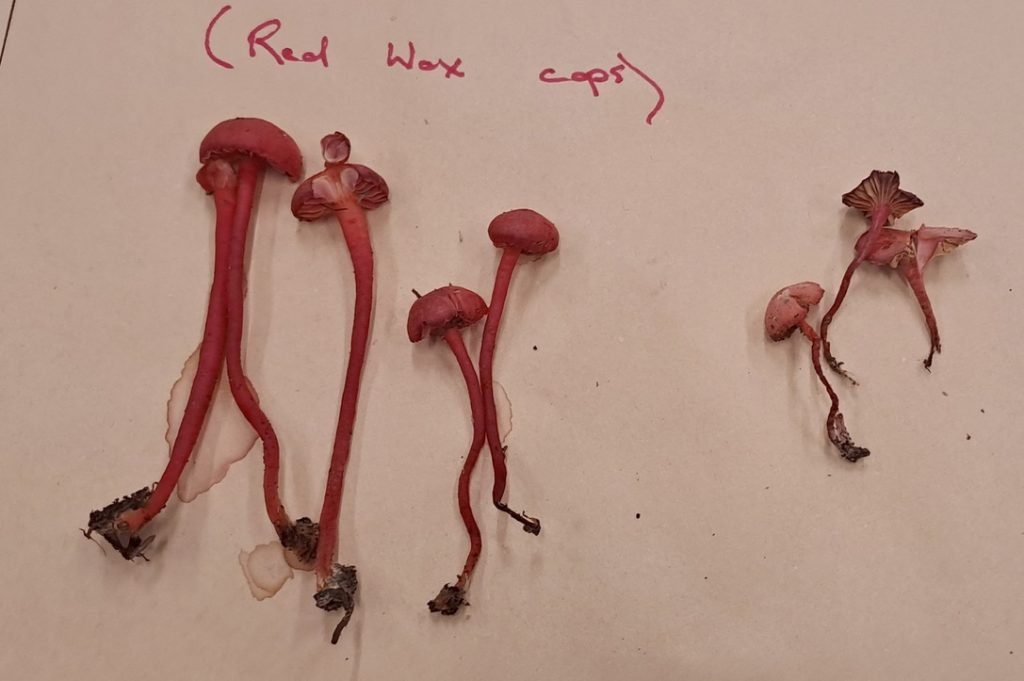

Gemma also has a collector’s license and had spent the previous few days collecting in the Greater Blue Mountains. Her keen eye found fungi in every colour, size and shape: edible, toxic, weird and wonderful. Workshop participants could get to know the fungi up close, which was particularly useful given one of the key identifying features is smell. Michael and Gemma generously shared their knowledge and enthusiasm, all the time ensuring that fungi were handled with care, or not at all, given the toxicity of some specimens.

Fungi collected and identified by Gemma Williams displayed at the workshop. The bowl in picture 3 is made from fungi in a process similar to papier mache. (Tracie McMahon)

Gemma found dozens of specimens in the local area, but explained that this is only a tiny sample of the diversity of fungi found in Australia. Ecologist Alice Blackwood, Field Technician at Western Sydney University, shared some tips for taking good photos of fungi for citizen science observations using iNaturalist.

For fungi, it’s particularly helpful to take photos from multiple angles (e.g., above, from the side, and from below), and to include a scale where possible. A small mirror can be helpful to show the underside of a mushroom without disturbing it. Alice also introduced workshop participants to Fungimap, a not-for-profit organisation which records and maps fungi in Australia. As with iNaturalist, it has reams of valuable information and stunning photos of fungi.

As the workshop finished, the audience was given time to quiz the specialists. The first question asked was: “What can we do to ensure fungi survive?”

Michael, Gemma, Alice and Steve were clear: look after the bush and take only photos. Fungi live on the ground, beneath our feet. When we walk into natural environments from urban areas our shoes can carry pathogens, such as phytophthora and myrtle rust, as well as invasive introduced fungi. Plant diseases and introduced fungi threaten native species.

It is very simple to stop their spread with good hygiene. To clean shoes or boots use a boot cleaning station if one is available. In the Blue Mountains you will need to carry cleaning equipment with you as there are few cleaning stations due to multiple access points to natural areas. Brush off any loose material on the shoe tread with a scrubbing brush, then spray the tread with methylated spirits or a solution of 10% bleach and water and leave for 20 seconds to dry.

Take Action:

- Learn more about fungi in the Central West and Central Tablelands with the NSW Government Local Land Services guide: https://www.lls.nsw.gov.au/regions/central-tablelands/key-projects/fungi-guide. A map and resources about fungi in Australia can be found at fungimap.org.au

- Visit the Atlas of Living Australia to learn more about local sightings. If you would like to add to the database with your own sightings, you can use the iNaturalist app. A guide to using iNaturalist can be found here https://www.inaturalist.org/pages/getting+started. Our previous article on citizen science at Lake Pillans also contains information on iNaturalist.

- Get permission to collect fungi. In National Parks you need a National Parks and Wildlife Service scientific licence and if you are collecting on private, crown or council land you need written permission from the land manager.

Share this article:

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.

One comment

Pingback: Postcards from the Past, Present and Future - Lithgow Area Local News