Maldhan Ngurr Ngurra Lithgow Transformation Hub on the corner of Bridge and Mort St, nestled against the Union Theatre. (Tracie McMahon)

By Tracie McMahon

Many local residents have been surprised to see Lithgow popping up as a backdrop on ABC TV’s The Messenger, as the fictional town of Moledale. Perhaps the ‘outside-world’ has finally caught on to our stunning urban heritage! This is the story of one of our prized buildings and the community that built, maintained and restored it to become the Maldhan Ngurr Ngurra Lithgow Transformation Hub.

Lithgow’s streetscape is a legacy of its industrial past. In the early twentieth century, when Australia needed coal and steel to build and power the railways and factories of a growing economy, Lithgow’s coalfields made it an industrialist’s dream. When the first pour of steel in Australia took place at the Blast Furnace in 1901, it seemed that Lithgow’s future was secure, safe from becoming the ghost town so many of its gold-rush neighbours had. People imagined a town bursting at the seams and were determined to provide facilities that would meet its needs and attract workers.

These dreams came to shuddering halt in the late 1920s when the Blast Furnace operations relocated to Port Kembla, followed by the Great Depression. However, ornate buildings constructed in a climate of economic ambition remained. Over time many were repurposed as Lithgow responded to the changing pressures of an evolving community.

The cost of maintaining and adapting heritage buildings is a challenge for any small community and must be balanced against other demands. It becomes a Waste to Art challenge on a grand scale!

This is the story of one of Lithgow’s buildings: the Hoskins Memorial Institute, and its metamorphosis into Maldhan Ngurr Ngurra Lithgow Transformation Hub.

The transformed building – a pictorial walk through

If you were born before 1980, chances are you refer to the Hoskins Memorial Institute as the ‘old Library’. Perhaps, like me, you also hadn’t appreciated the building itself. I found it a bit ‘boring’ compared to the gothic architecture of the nearby Hoskins Church. I hadn’t been back inside since Western Sydney University signage went up. But as I wandered past one day, the door camera caught sight of me and the big glass doors opened. I turned back and peered in.

A sandwich board at the bottom of the steps invited me inside. It described the Maldhan Ngurr Ngurra Lithgow Transformation Hub as “a collaborative space for community, business and industry to come together and explore a wealth of possibilities for the Lithgow region to ensure a vibrant and thriving future.”

I climbed the steps and the second of the glass doors slide open. I could not believe what I was seeing. I had to stop and turn around to check it was still this building. The dingy cornices and bookshelves I remembered had disappeared. Stripped bare, I could now see high ceilings, heritage architraves and smoothly plastered walls painted pearlescent white. Nine small squares of glass that comprised the window over the entry to the old children’s library remained, and I was disorientated as I stepped under it to see a room filled with neat tables, comfortable chairs and a corner office. It is modern and airy. There is no longer a dark alleyway leading to ‘the stack’ but a light filled corridor and enormous windows that showcase an internal courtyard, clothed that day in glorious Autumn colours.

The central courtyard nestled into the junction of the building wings. (Tracie McMahon)

A friendly staff member popped her head out to ask if she could help. In response to my many questions, she offered to organise a tour with Karen Purser, the new Manager. So, I returned a few weeks later, eager to see what else had changed.

Karen is equally impressed by the venue. She tells me she is amazed at the facilities and programs she now manages. They include a lecture theatre, training rooms, a digital communications room, a wet science lab, a clinical simulation room, collaboration spaces, and a self-contained flat for visiting presenters.

The 90-seat lecture theatre, showcasing the gardens and architecture of Hoskins Church. (Tracie McMahon)

The spaces are all state-of-the-art and comfortably furnished. Walls are adorned with local art, depicting Lithgow landscapes, natural and built. Many of the pieces honour local people and stories.

A panel of the large artwork that adorns a corner of the office space. The caption describes the ‘love story’ of the artist’s parents: a Hungarian POW and an Australian woman who met at the end of WWII, in Littleton Hostel (Artist: Rachel Szalay)

A corridor overlooking the courtyard is lined with local artwork by Caitlin Graham recording the demolition of Wallerawang Power Station (Tracie McMahon)

Since its transformation to the Hub, it has been used as a regular meeting space for the Lithgow Business Chamber, provided a temporary base for the Zig Zag Railway and is now home to the Lithgow Valley Voices Choir. Other businesses and not-for-profit groups use the space for workshops, meetings, or events.

The facilities are available to all, you do not have to be a WSU student, or a member of any group. There are co-working spaces available for daily, weekly or monthly hire, or you can hire a room for collaborative work or client meetings. Costs vary depending on the facilities required and Karen Purser indicates that their prices are targeted to match their role as a community hub.

Karen Purser, Manager of the Hub, in one of the meeting rooms. (Tracie McMahon)

Western Sydney University coordinates programs and workshops from the Hub. In 2023, they have offered a digital storytelling project for school children and citizen science projects such as Heat Mapping and the Lake Pillans BioBlitz. Upcoming programs include a second Bioblitz event, a ‘Painted River’ workshop, a Sustainable Housing Expo, and various other citizen science activities.

New programs and events are advertised on their Facebook and Instagram pages and on our Lithgow events calendar.

As I leave, Karen shows me the disability access lift at the street level entrance and offers me use of the carpark at the rear next time I visit.

The refurbished entrance foyer to the Hub is fully accessible. (Tracie McMahon)

The juxtaposition of heritage architecture with artwork highlighting young community voices, gave me pause to consider the story of the building and its previous occupants. I wondered what had gone before. Had it always been a place of community and conversation and how had this building attracted the funding for such a transformation?

I was fortunate that a past Lithgow librarian shared my curiosity. The staff at Lithgow Library and Learning Centre directed me to a paper presented to the Lithgow District Historical Society in 1980 by L. Petocz, detailing one hundred years of library service in Lithgow.

I found answers to many of my questions from this article, together with records held at Eskbank House Museum and a seminar given by Associate Professor Louise Crabtree-Hayes of Western Sydney University’s Institute of Society and Culture.

My research yielded the story of a building that is not only bricks and mortar, but a manifestation of Lithgow City, a place which has evolved many times to meet the needs of its community.

A history of the site

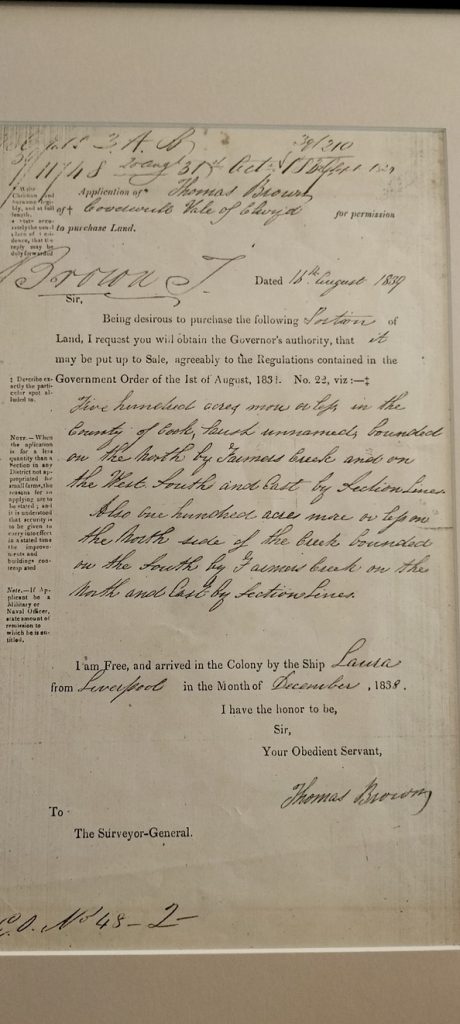

The Hub is located on Wiradjuri land. The land was never ceded, but it was given as a colonial land grant to Thomas Brown in 1838, becoming part of the 500 acre Eskbank Estate. There is little recorded history of this era, as Brown instructed that his papers be destroyed on his death. The only surviving records are by visitors to the estate, who remarked on Brown’s passion for the region:

“For many years past, Mr. Brown has relieved the monotony of his magisterial duties by minutely studying the formation of the rugged and desolate scenery around him; and to one who loves such studies, a better field could not be presented than this parish, with its gold, its irons, its jewels and its coals” (W. Hamilton Henderson, A Policy Magistrate’s Museum in the Australian Bush, Empire, 16 June 1865).

Copy of the application for land by Thomas Brown. Courtesy: Eskbank House Museum

Eskbank House signage describes the railway coming to Lithgow in 1869, via the great Zig Zag engineering feat. The estate transformed into a working coal mine, the house becoming an “island in a sea of industry”.

In 1901, a group of locals approached William Sandford (then owner of Eskbank Colliery) to donate land to construct a new School of the Arts. Petocz’s research suggests that in the 1830s, there was an Australia-wide School of the Arts movement, which grew from the belief that “moral improvement came through the acquisition of useful knowledge”.

In 1907, the foundation stone for the New School of the Arts was laid and the opening celebrated with a ‘Conversazione’ and dance in the Oddfellows Hall, now known as the Union Theatre. The building contained a billiard room, draughts and chess club, library and reading room. They offered a subscription-based library service only allowing paid-up members and their guests to enter the building.

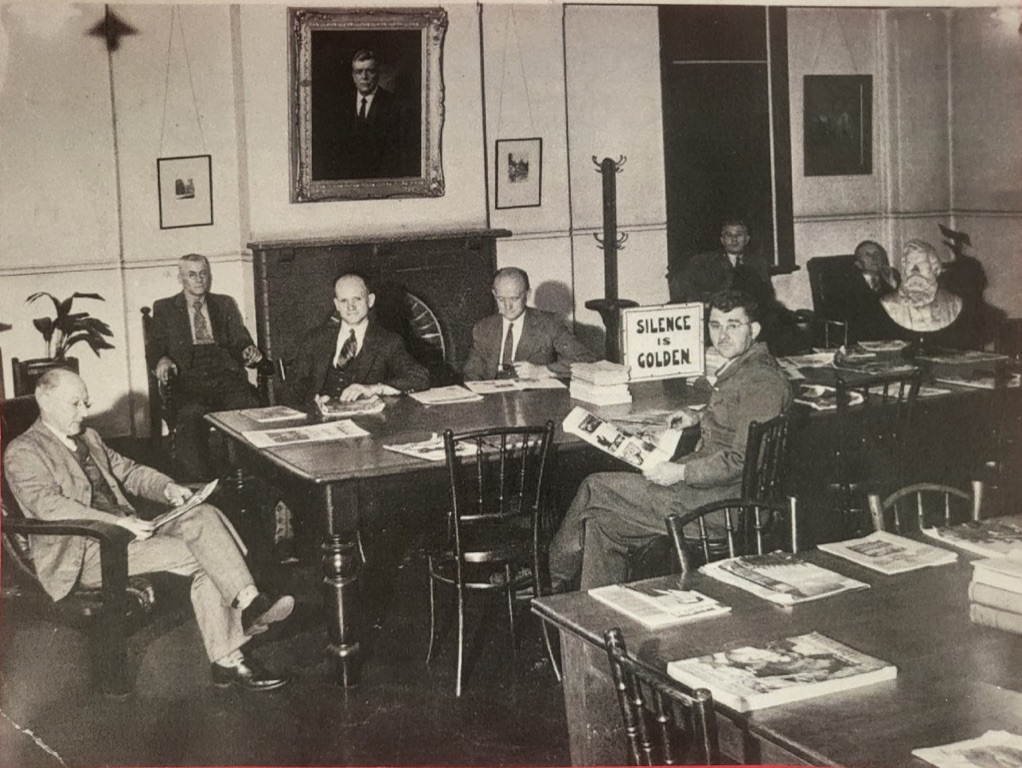

The reading room New School of the Arts, circa 1910. Note the fireplace. This is the meeting room in the photo with Karen Purser above. No longer is it a room where Silence is Golden. (Courtesy Lithgow Library and Learning Centre)

The building later became the Lithgow Literary Institute, reported by the Lithgow Mercury in 1917 as “a place for young men where they can spend their evenings with pleasure and profit, after the hotels were closed”. It was equipped with telephones in 1919 and electric lighting in 1920, with power supplied by prominent Institute member Charles Hoskins, then owner of Eskbank Estate.

When Charles Hoskins died, his family offered to construct a new Literary Institute in memory of their father. The old building was demolished, and the site transformed into the Charles H Hoskins Memorial Literary Institute.

That building is the bricks and mortar of the current Hub. When it appeared on Lithgow’s streetscape in 1927, the Lithgow Mercury reported “the external appearance is somewhat disappointing”. First impressions were quickly overridden by the interior, which was declared an “architectural triumph”. They described its many features with pride: “Apart from the library, the new building included lecture and meeting rooms, ladies lounge, social hall, billiard rooms, card rooms, a gymnasium and a caretaker’s quarters, and was furnished and equipped ‘lavishly’”. Reading this, I realised that the contemporary architects had considered the building’s history in their plans.

The 1920s optimism for Lithgow’s future was short-lived. The relocation of Hoskins Steel Works and the demands of the Second World War led to turbulent times. However, during the 1940s, the NSW Library Act provided for free libraries, opening the door to the building’s next incarnation.

In 1943, the Lithgow Municipal Council approached the Hoskins Memorial Institute about establishing a free reference library. The request was declined, but the idea wasn’t abandoned. In 1947, the Principal of Lithgow Public School approached the Joint Coal Board to garner support for a children’s library. The Board agreed, provided they find a suitable space. The Hoskins Memorial Institute was identified and negotiations between the Council and the Institute began. Despite initial resistance from the Institute’s management committee, the building was transferred to the Council to establish a free community library and children’s library, the latter supported by the Joint Coal Board.

Once again the site had evolved to meet community needs, this time made accessible to all.

Over the next six decades, the Lithgow Library grew. It began providing regionalised library services to the neighbouring Blaxland, Rylstone and Oberon Shires with branches in Portland, Wallerawang, Rydal, Kandos and Oberon. Each expansion came from community requests, often spearheaded by a Parents and Citizens Association, eager for their children to access a library service.

Children at the Library circa 1970s. (Lithgow Library and Learning Centre Collection)

In 2004, the renamed Lithgow Library and Learning Centre relocated to Main St, with branches in Wallerawang and Portland. The old building continued to be used by other groups such as the State Emergency Service, Lithgow Theatre Group and the Senior Citizens Association.

In 2012, it was leased to Western Sydney University to establish a regional campus. An extensive renovation was funded by a federal government grant supporting the University’s UWS College operations. The Lithgow Campus opened in February 2014, offering foundation studies and diploma programs in engineering, science and arts. In December 2018, course delivery ceased, and the University began considering alternative uses for the building.

Maldhan Ngurr Ngurra Lithgow Transformation Hub comes into being

In 2019, fifty invited stakeholders, including many locals, attended a two-day workshop facilitated by the University, to determine future uses of the site. In a recent presentation, one of those workshop facilitators, Louise Crabtree-Hayes, described the process: “By lunchtime on day one, we upended the agenda and went for a walk around the building, then returned to form groups to discuss the possibilities. From here we were able to determine a vision and strategy which was co-designed.”

The walls of this historic building had again echoed with the voices of community and evolved in response to its needs.

The official opening in April, 2021 (Lis Bastian)

In April 2021, the site reopened as Maldhan Ngurr Ngurra Lithgow Transformation Hub. The name was gifted to the Hub by Aunty Sharon Riley of the Mingaan Wiradjuri Aboriginal Corporation, during the community engagement process. Signage has been erected in the building to honour that gift, explaining that it is “a Wiradjuri expression broadly meaning workmanship side by side”.

As I reflect on the story of this building, it occurs to me the name gifted to this important site is fitting. This building, and the land on which it sits, have always carried the stories of workers: from collieries to school children to adults striving to learn and work for the betterment of their community. Side by side they have transformed this building, ensuring it continues to evolve to meet the needs of Lithgow’s community.

If you would like to obtain further information or use the facilities, the Hub can be contacted on (02) 6354 4505. A brief overview is also available at https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/future/our-campuses/lithgow-campus.

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.