Hans and Tillie Coster in front of their underground house at Middle Earth, Lithgow (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Story by Lis Bastian

In my fantasy world I’ve dreamt of leaving the City and finding a block of land on a river where I could plant trees, grow food and live a self-sufficient off-grid life. In this fantasy I’d build a beautiful home, deep into a hill, so that I could withstand anything the future threw at me: hurricanes, extreme heat or cold, flood or fire. I was filled with delight when I heard that Hans and Tillie Coster had done just that, and more, bringing a Tolkien fantasy to life as they built an underground Hobbit Hall at their property ‘Middle Earth’ in Lithgow. I couldn’t wait to visit.

Key Points:

- Building underground means that the walls and roof are in contact with the surrounding earth which is at an all year-round temperature of 14C regardless of freezing winters or sweltering heatwaves. It also helps withstand high winds and increases protection from fire.

- Replanting trees creates cooler microclimates, increases biodiversity and helps protect our atmosphere.

- Nickel-iron batteries are a long-term solution for storing solar power because they’re virtually indestructible.

Hobbit Hall uses science to make fantasy a reality. It’s a spacious two-storey home (and a laboratory), built into a hillside. It’s surrounded by regenerated bushland, rich biodiversity, and overlooks a river.

Hans and Tillie Coster have come very close to achieving self-sufficiency. They filter water from the river, they have a composting toilet, and their power, for both house and car, comes from solar panels which feed a bank of Nickel-iron batteries that will outlive most humans! (Read more about these batteries later in the story).

Middle Earth also has a large greenhouse in which they grow food and native seedlings.

Underground and Off-grid at Middle Earth (Video: Kalani Gacon)

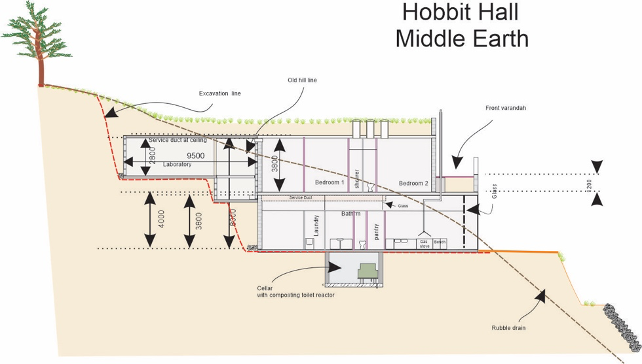

Elevation showing how Hobbit Hall has been built into the hill with 1 ½ metres of soil on the

roof. (Image: supplied)

The entrance to Hobbit Hall: the hill is on either side and 1 ½ m of soil is above the roof (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Professor Hans Coster is a Physicist who has worked for both the University of NSW and the University of Sydney in the fields of Biophysics and Bioengineering. In the 70s he was also in charge of the Sydney Chapter of the Club of Rome, which brought together leading scientists, economists, and businesspeople to address pressing global issues like the limits to growth on a finite planet.

“The computation facilities we had were nothing like what we have now,” said Hans, “but a lot of the predictions have come true. We were focused on pollution, population growth and energy generation. You know if we have more than a 4-degree temperature rise we’ll lose our atmosphere.”

Hans gave several seminars on the Thermodynamics of Planetary Temperature Balance. “I was concerned about planetary heating and the role of the overall biosphere and human industrialisation.”

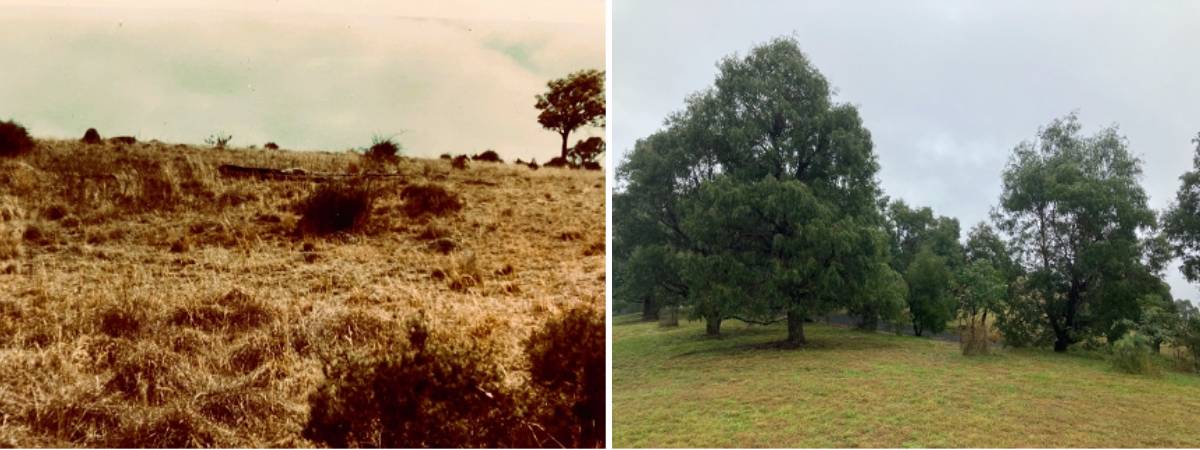

Concerned about the health of the environment, in 1976 he and his wife Tillie, a primary school teacher, bought 60 acres of degraded sheep country on the Cox’s River in the Kanimbla Valley. On weekends they travelled up from Sydney, camped and began planting trees. Forty-eight years later they are now surrounded by extensive bushland and extraordinary biodiversity.

Left: Middle Earth in 1980 and (right) in 2024 (Photos supplied)

Before and after…. (Photos supplied)

Looking from the house down to the river at some of the thousands of trees that they have planted over 48 years. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Another view of the forest they’ve planted. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

We were delighted by the song of a tree creeper right next to the house on the day we visited. (Video: Lis Bastian)

Building Hobbit Hall

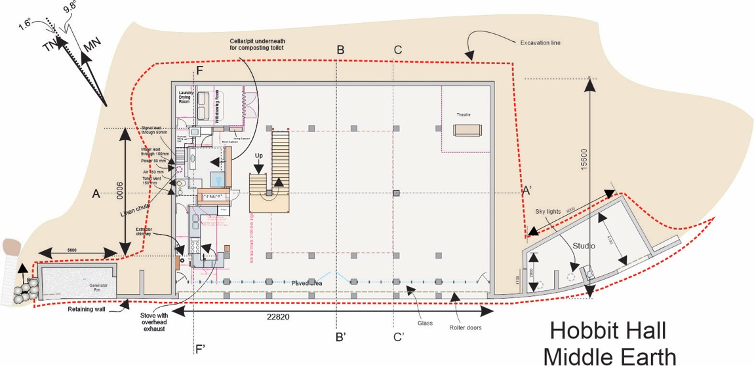

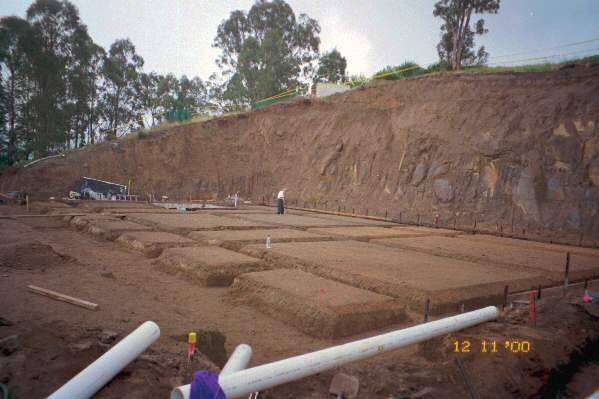

In 1995, after nineteen years of camping and tree planting, Hans and Tillie had a large hole excavated into the hill at the top of their property to begin building Hobbit Hall. They wanted to build a home that would withstand extreme weather events. Building underground meant that the house temperature would be moderated by the having the walls and roof in contact with the earth which is at an all-year-round temperature of 14C regardless of freezing winters or sweltering heatwaves. It could also withstand high winds and be protected from fire. They began pouring concrete in 2000.

Hans and Tillie then worked on all aspects of the building, including internal carpentry, over the seventeen years it took before they could finally move in.

Before they finished their windows they closed the building with roller shutters. Now these roller shutters cover the large glass doors and windows at night to help keep the temperature regulated. They also help protect against fire.

Tillie tying steel for the roof (Photo: supplied)

Hans did all the carpentry in the house, including the stairs (Photo: Lis Bastian)

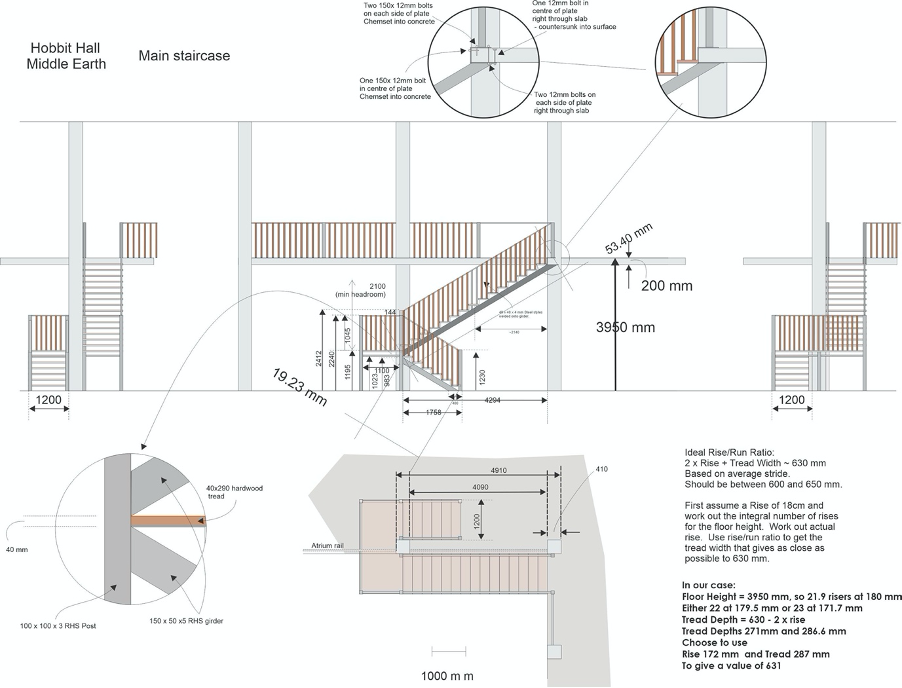

The stairs were built using the ideal rise/run ratio for the average stride, a ratio originating from ancient Greece and rediscovered by his daughter Adelle. (Image: supplied)

The Clivis Multrum composting toilet was factored into the build to allow for a long drop of 8metres. It’s crucial for saving water. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

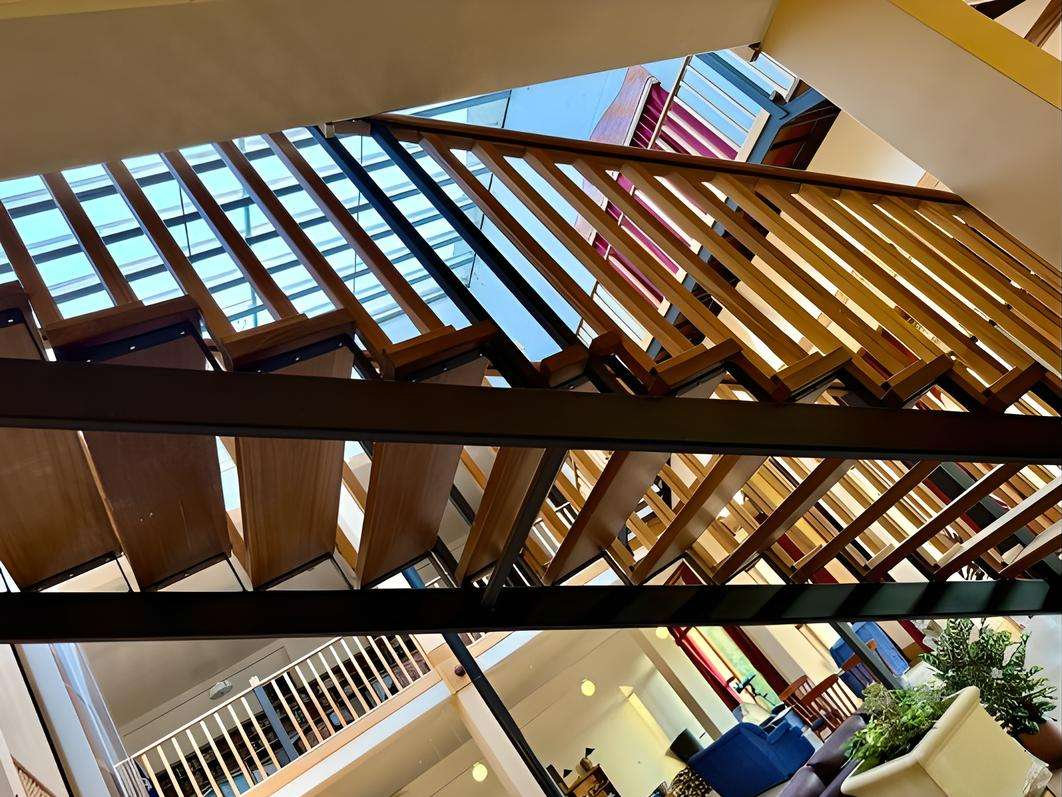

Despite being underground, Hobbit Hall is bright and airy thanks to the Atrium built from 10mm laminated glass wall partitions rescued from the Telstra Tower in Sydney when it was being renovated.

A view of the atrium letting in light through the stairs Hans built. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Light pouring in through the atrium. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

During the wet weather events of recent years water was literally oozing out of the hillside but, despite being underground, their house stayed dry because of the waterproofing they did during the build. (Read more about how they built the house later in this story.)

After coming up weekends, then three days and four days for many years, Hans and Tillie left Sydney permanently to live at Middle Earth when COVID started.

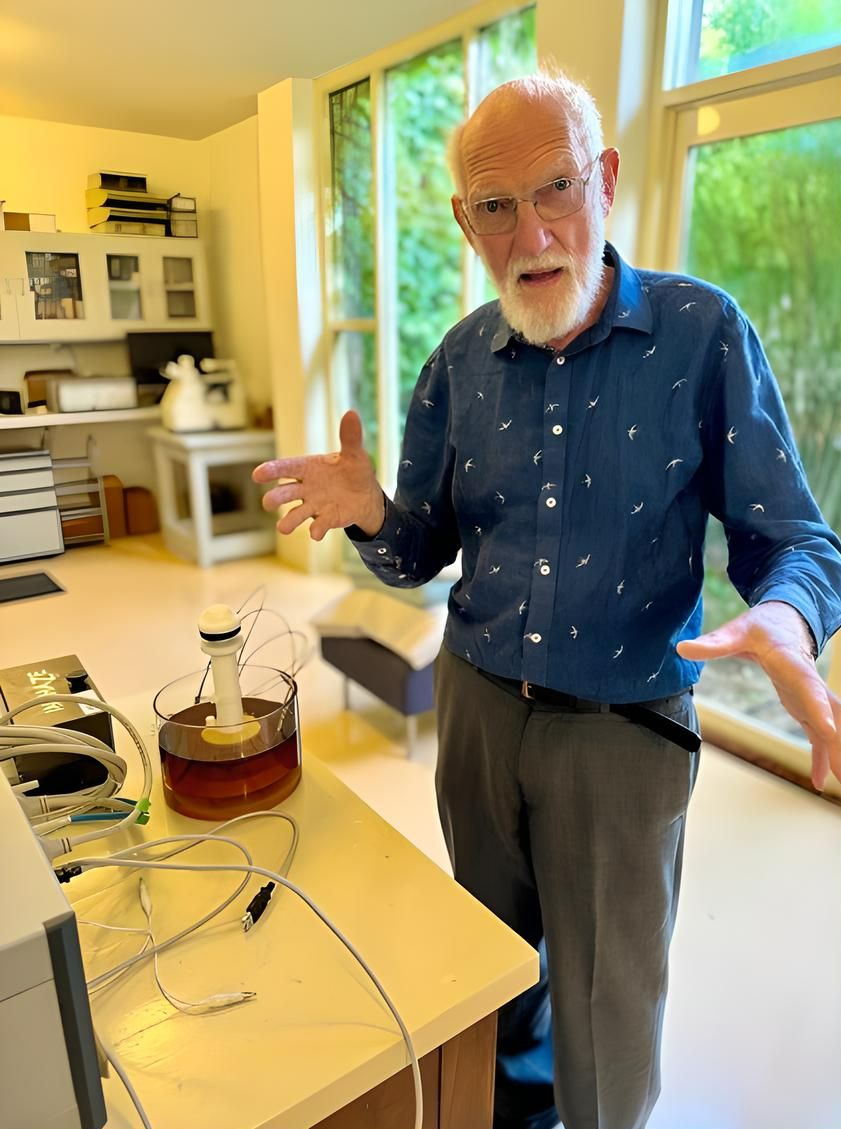

Hans in his Lab measuring how much water is in oil. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Hans continues to work in his Lab where he’s currently developing permeable membranes and a technique for measuring how much water is in oil.

Tillie’s passion is gardening. Inspired by the ancient Greeks, Hobbit Hall has a peristyle (a covered walkway surrounding a courtyard) where Tillie has created a beautiful garden.

The peristyle garden. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Looking down from the roof of Hobbit Hall into the peristyle garden. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

She also collects native seeds and propagates them in the greenhouse to regenerate the rest of the property.

Tillie in her greenhouse where her passion is propagating native species. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Some of Tillie’s seedlings in the greenhouse. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Tillie loves using the rocks on the property to create resilient garden beds (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Tillie’s vegetable garden. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Just a few remaining of this year’s pumpkins, after distributing many to friends and family. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Water is pumped up from the river to this tank. It then gets filtered. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

This lift sucks! (Video: Lis Bastian)

Recently, to provide a backup if either of them cannot negotiate the stairs, Hans and Tillie installed an air powered lift which consumes less energy than a home appliance.

A small motor at the top of the lift sucks out 10% of the air and air pressure then pushes the lift up. In the event of a power failure the cabin slowly descends to the ground floor as the pressure equalises.

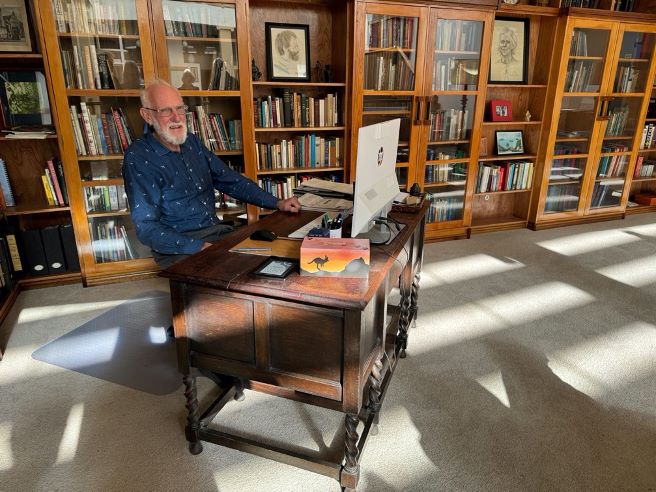

Hans sitting at Tillie’s desk in the library he also built. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Solar Panels and Nickel-Iron Batteries

18KW of solar power. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Hobbit Hall, and their electric car, are run on 18KW of solar power that is stored in a double battery bank of Nickel-iron batteries. Hans chose Nickel-iron because of their long life compared to Lithium-ion batteries. He showed me photos of cars built by Edison:

“These were the cars that Edison made and they used these type of batteries. And that was 1905. And his batteries are still working. That was a big consideration for me.”

Hans talking about why he’s chosen Nickel-iron batteries (Video: Lis Bastian)

More on why Hans chose Nickel-iron batteries (Video: Lis Bastian)

Nickel-iron batteries in the shed (Photo: Lis Bastian)

“I do like Lithium-ion batteries. I think they have lots and lots of advantages but the fact that they have a very finite lifetime was a negative for me. I wanted something that was going to last and these batteries are basically indestructible. You can store them completely discharged for years and they’ll spring back to life. You can overcharge them. They don’t care about that either. They are very robust.”

“But they have some disadvantages because the chemistry is such that water gets electrolysed and it doesn’t actually take part in the electricity generation but it gets electrolysed in the process and that means you’ve got to keep topping them up and that’s a real pain in the neck. I was doing that manually to start off with: every week going along and putting a half a litre of water on each battery and that becomes a real pain in the neck.”

“So I then installed an automatic watering system that does it for me and that’s supplied from that tank which is reverse osmosis water. I had to put in a little reverse osmosis system because it has to be very pure water. So one thing leads to another but it’s working well at the moment.”

I asked Hans for more information about these batteries:

“The batteries need a lot of “conditioning” before they achieve their rated capacity. That can be (and was for me) a problem because you need to charge them as rapidly as possible and discharge them quickly in a cycle. Even discharging them actually presents some challenges.”

“The batteries are not really suitable for vehicles because they are too bulky and heavy. Lithium batteries have a much higher energy density (both in weight and volume). When Edison built his electric cars, Lithium batteries had not yet been invented and the best there was, was the Nickel-iron batteries. This battery was invented in Sweden but never made commercially until Edison developed it for his electric cars in the USA. The batteries worked fine with the cars he made; the performance of cars was not anything like we have today. It was a time when steam cars were around.”

“The Nickel-iron batteries are very suitable for houses but do require some additional infrastructure such as water replacement etc and require more flexible charge controllers and inverters (to take it back to 240v AC) than Lithium batteries. But they are actually considerably cheaper, are extremely robust and last a very long time (more than 120 years!).”

“It is interesting that you have discovered some Australian suppliers. They weren’t around when I bought my first set, so I imported them direct from a manufacturer in China. The second lot I bought recently were from the same manufacturer; they were easy to deal with and helpful. Importation into Australia on a one-off basis is quite complicated but I sought the assistance of a freight/import agent and they were good and not expensive. The second time around was a lot easier!”

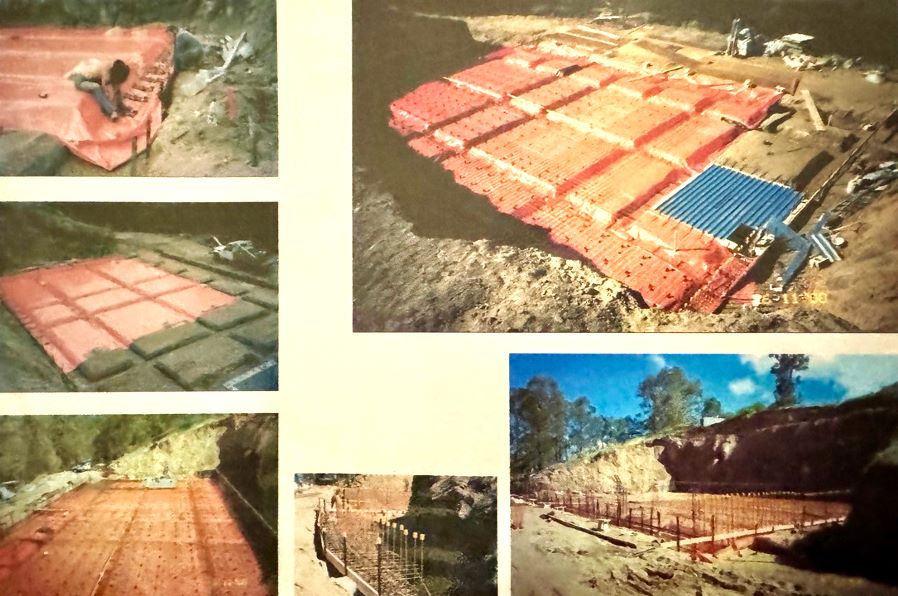

The Construction of Hobbit Hall – in Pictures

Ground floor plan showing how Hobbit Hall was cut into the hill

Main pad trenches with Tillie clearing rock shards. (Photo: supplied)

Waterproofing the foundations. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

Pillars first fill March 2001. (Photo: supplied)

Funnel for the gravel (lower right). (Photo: supplied)

Formwork for the roof. (Photo: supplied)

Formwork for the roof. (Photo: supplied)

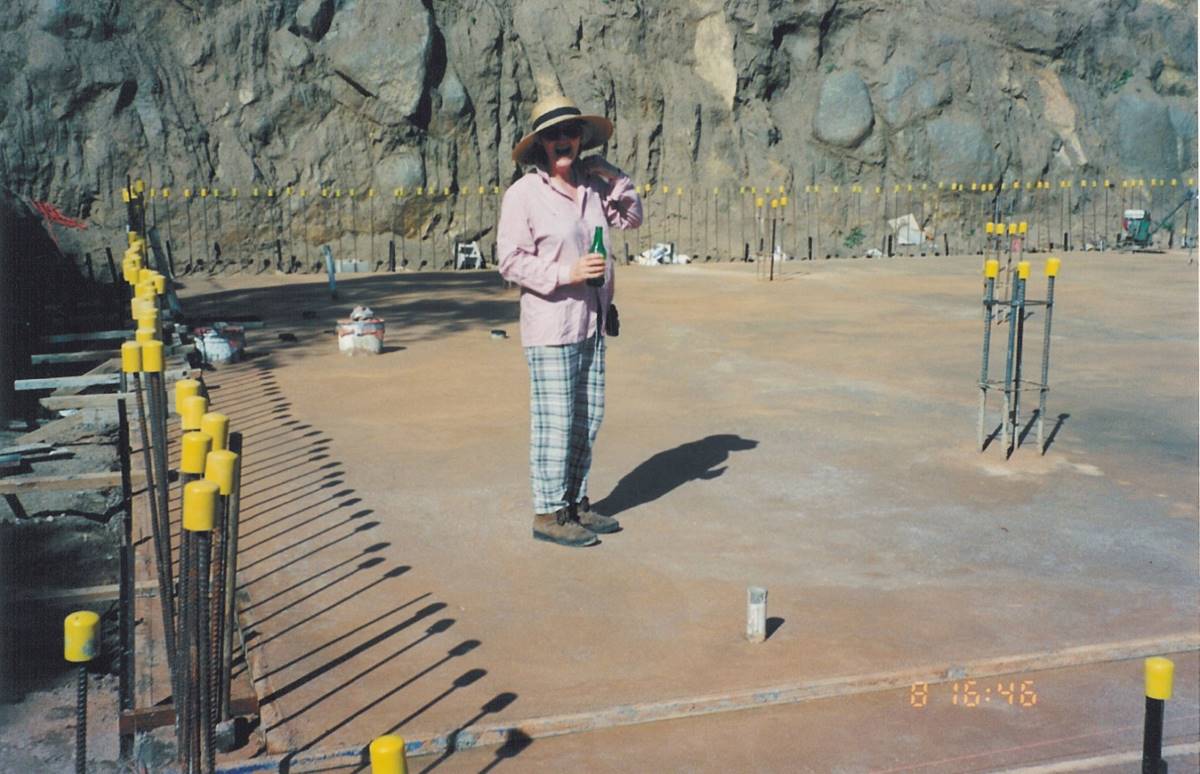

Tillie having a beer on the finished ground floor (Photo: supplied)

First storey, June 2001. (Photo: supplied)

Hans applying four layers of waterproofing butyl rubber (4mm thick) to the roof. (Photo: supplied)

Placement of Styrofoam panels over butyl rubber coating. The extruded polystyrene fitted closely together and the tongue and groove was sealed with more of the butyl rubber coating (Photo: supplied)

Top view of completed backfill to first storey. (Photo: supplied)

View from the back wall (Photo: supplied)

Waterproofing walls showing plastic drainage panels over Styrofoam panels (Photo: supplied)

Pat, Tim and Hans constructing the window frames. Until they were built the roller doors were the only doors!

The finished roof with Hans pointing to their internet tower. (Photo: Lis Bastian)

After spending time with Hans and Tillie, I left feeling confident that, after all, humans might well be smart enough, and if inspired as I was by what they were doing, eventually committed enough, to restore the health of our planet.

Share this article:

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.